J'Accuse! The Kabul Regime aided ISKP

Open-source evidence suggesting that the US-backed Kabul Regime patronized ISKP as a bulwark against the Taliban

September 2019: Taliban commander Tawhidullah Soleiman beheads a senior ISKP member in Kunar during the massive Taliban - ISKP showdown in the region from 2019 to 2020. Soleiman was later killed in a drone strike on 11 May, 2020 after attacking a large convoy of ANA forces. This ended his long career in the Taliban, which he had joined as a teenager.

Some months ago, I went on Radio War Nerd to discuss the evidence I have collected over the years which together strongly suggest that the US-backed Kabul Regime supported ISKP as a bulwark against the Taliban. During the episode, I relied on a set of extensive notes that I had quickly drafted up the night before recording. Since recording, I have discovered additional evidence, so I have decided to turn my notes into a formal article, replete with audio-visual and textual sources. It is a very lengthy piece but I promise it is worth the read. Be sure to check out my sources. I hope you enjoy and I hope the FBI doesn’t suicide-gun me for it. To Ashraf Ghani, Amrullah Saleh, Abdul Rashid Dostum, and all their stooges, I say: J’Accuse!!

Salafism in Afghanistan

Salafism (and Salafi Jihadism) is a new school of Islamic thought in Afghanistan and it has always been a small minority among Sunni Afghans.1 Arab foreign fighters introduced Salafism to Afghanistan during the anti-Soviet jihad in the 1980s. Afghan mujahidin largely found Salafism bizarre and ultra-puritanical since the vast majority were Hanafi, which is the biggest mainstream Sunni school of thought. The Pashtun fighters in particular were Deobandi, a subset of Hanafism, which is especially Sufi-inflected. This puts it at odds with Salafism, which harshly opposes the more mystic elements of Sufism. The most (in)famous Deobandi group in Afghanistan is the Taliban, whose members have always been overwhelmingly Deobandi and quite suspicious of Salafism and its adherents. Indeed, during the original Taliban regime, they harshly repressed Salafis and forbid its proselytization. Mullah Omar himself was suspicious of Salafism and accused it of heresy. Taliban members have often contemptuously referred to Salafis as ‘Wahhabis,’ from Muhammad ibn Abdal-Wahhab. Naturally, this irritated the Arab Salafi Jihadi fighters active in Taliban-controlled territories. At one point, top Al Qaida leader Abu Musab al-Suri–who was the most sympathetic to the Taliban–wrote a pamphlet defending the regime, strikingly titled, ‘Are the Taliban Ahlus Sunnah [Sunni Muslim]?’2 The fall of the Taliban regime did not necessarily force them to revise their views. One prominent cleric in the movement asserted that Wahhabis are the worst unbelievers in the world, even worse Jews and Crusaders.

‘Khawarij’ refers to an early violent heretical sect in Islamic history. The term has become a political term of abuse within Islamism to refer to groups one considers to be extremist.

At the same time, many Salafi militants fought in the Taliban as it was the only Islamist insurgency combatting the Coalition and its Afghan quislings. This led to clear tensions, which were exacerbated by the Kabul Regime’s loosening of restrictions on Salafism. The government allowed open proselytization and practice, which led to overall growth in Salafism. In other words, their extreme beliefs could grow only under a liberal government, which likewise facilitated the relative ascendence of Afghanistan’s Shia minority, whom Salafi revile. Meanwhile, the Taliban did not respect their beliefs and kept them in low ranks. This dynamic left Salafi Afghans in an odd limbo, which finally changed with the emergence of ISKP, a stridently Salafi Jihadi organization willing to fight for Salafism as such. So how did ISKP emerge?

ISKP’s Origins

2015: ISKP commanders propagating the message of Islamic State and its goals to villagers in Achin, Nangarhar

Within the Taliban, there are Afghan and Pakistani branches, the latter called Tehrik e Taliban Pakistan (TTP). They form one movement with the same ultimate emir (leader) albeit with quite organizationally different constituent parts. TTP has always been much more decentralized than the Afghan Taliban, especially before the leadership of current TTP emir Noor Wali Mehsud, appointed in 2018. Prior to that year, TTP was a loose coalition of different affiliate groups with overall similar aims but often quite different ideological worldviews. Most groups were ideologically identical to the Afghan Taliban while others, particularly in Orakzai Agency, were stridently Salafi Jihadi (or Panjpiri, an adjacent school). These latter TTP groups had much greater organizational strength and respect than their Afghan Salafi counterparts since they had long been favored by TTP leadership. Further, by late 2014, non-Salafi TTP groups had lost significant influence and power due to Pakistani military operations, which forced TTP to rely on its Salafi Jihadis, giving them special influence.3 ISKP emerged from these radical splinters of the TTP, but the way it emerged is disputed.

Antonio Giustozzi proposes one theory in his book Islamic State in Khorasan. Giustozzi argues that key figures in TTP who later formed ISKP, like Hafez Saeed Khan, sent large detachments of foreign fighters to Syria to fight under Jabhat al-Nusra, which was Al Qaida’s official Syrian branch. These efforts were generously financed by both Al Qaida Central and Islamic State of Iraq (IS’s predecessor) – but why? Giustozzi argues it may have been because IS/AQ had already made plans to spread the Syrian project back to Khorasan (Afghanistan-Pakistan region). The plan worked but not smoothly, as there were several different IS-aligned Salafi Jihadi groups that later merged to form ISKP. This theory is interesting, but I find it unconvincing. Hudson Institute provides a better structural account of the split than Giustozzi.

In Hudson Institute’s telling, ISKP emerged as a mainly anti-Pakistani force before quickly shifting into an anti-Taliban force. In October 2014, Hafez Saeed Khan and other top TTP leaders (including the central spokesman Shahidullah Shahid) defected to IS and declared ISKP.

When it was inaugurated, Khan declared that ISKP would revitalise the TTP’s stagnating war in Pakistan and called on members of the TTP to join his new group, a show of strength that simultaneously attracted a number of Afghan Salafists to the cause despite being initially Pakistan-focused. This all happened at an especially opportune moment for ISKP: At the time, the TTP was suffering from major internal rifts due to disagreements regarding its terms of engagement with the Pakistani government. As a result, hundreds of TTP members ended up defecting to join ISKP in the weeks that followed.

When the Pakistani military deployed a slew of aggressive military operations against the TTP within a matter of weeks of these defections (although not because of them), ISKP shifted its headquarters to the Afghan side of the border, specifically Nangarhar province and adjacent Kunar province. There, it picked up a large number of disenfranchised Salafist militants that were until then in the ranks of the Afghan Taliban. [Many these local Salafi militants were also ‘ex-TTP’ who had settled in the area beginning in 2010 to flee the Pakistani military. See below for further detail. - R. Ashlar].4

Some six months later in May 2015, ISKP declared war on the Taliban allegedly ‘due to the Taliban’s persistently unjust and belligerent stance towards ISKP supporters that had fled from Pakistan earlier in the year.’5 The more likely reason is due to the Taliban’s support from the Pakistani state which ISKP virulently hated. In either case, ISKP quickly received the vocal support of prominent Salafi clerics in Nangarhar and Kunar, which attracted many local Salafi Jihadi fighters, thus diluting the original Pakistani composition of ISKP.

This gradual Afghanization of ISKP was accelerated by the targeting of its Pakistani leadership in drone strikes and joint raids of US and Afghan forces, operations that were augmented by increasingly aggressive counter-ISKP posturing from the Taliban. This saw ISKP transforming just one year on from its formal and public establishment in January 2015 into an Afghan-centric movement with the non-militant Salafi Afghan scholar Shaykh Jalaluddin acting as its chief ideologue and another Afghan Salafist scholar, Abdul Hasib Lughari, succeeding Hafiz Sa’id Khan as wali (Khan was killed in July 2016 in a US drone strike). This transformation attracted yet more Afghans to its ranks. Indeed, ISKP came to be seen as a vehicle to establish Salafist supremacy in Afghanistan, something to which Shaykh Jalaluddin directly alluded in August 2015 when he stated that ISKP was fighting for the same goal as Shaykh Jamil’s JDQS [first ever Afghan Salafist group] in the 1980s.6

With this context, Afghanistan Analyst Network’s (AAN)–the premier Afghanistan-focused analysis group–account of the fine details of ISKP’s emergence is perhaps the best and most scandalous.

2015: ISKP commander indoctrinating local children in Achin by showing IS Central propaganda, in particular, the highly graphic Camp Speicher Massacre film

AAN argues that the first ISKP fighters in Afghanistan were TTP militants who had long settled in Nangarhar to flee Pakistani state repression, starting in 2010.7 Initially, locals welcomed these militants under the impression that they were fellow persecuted Pashtuns. Locals soon realized they were something more dangerous they openly wielded weapons. Among these militants, the most prominent group was Lashkar e Islam (~500 fighters) led by Mangal Bagh. AAN’s account is worth quoting at length:

The Afghan government’s support to Mangal Bagh’s men is an open secret among residents of the Spin Ghar districts near the Durand Line. Residents from Achin recall the generous hosting of groups of long-haired Lashkar-e Islam fighters at the houses of Shinwari tribal elders, such as Malek Usman and Malek Niaz, in Achin. They had introduced their black flag to the area long before ISKP hoisted a flag of the same colour with different symbols and slogans. According to residents, Lashkar-e Islam’s flags were flying over many houses in the Mamand valley in Achin in the summer of 2014. Today, Lashkar-e Islam remains an implementing partner of ISKP in Nangarhar. Mangal Bagh’s fighters, mainly from the Afridi tribe, who predominantly come from Khyber Agency, have not actually merged with ISKP, but they act in such close coordination with it that many locals perceive them as having morphed into a wing of ISKP. [...]8

However, efforts by the Afghan intelligence service, the National Directorate of Security (NDS), to woo Pakistani militants in Nangarhar have not been confined to Lashkar-e Islam or to militants from Khyber. Tribal elders and ordinary residents of Achin, Nazian and Kot testify that fighters from Orakzai and Mohmand agencies belonging to different factions of the TTP have been allowed free movement across the province, as well as treatment in government hospitals. When moving outside their hub in Nangarhar’s southern districts, they would go unarmed. In off-the-record conversations with AAN, government officials have verified this type of relationship between segments of the Pakistani militants and the NDS, as have pro-government tribal elders and politicians in Jalalabad. They described this state of affairs as a small-scale tit-for-tat reaction to Pakistan’s broader and longer-ranging, institutionalised support to the Afghan Taleban in their fight against the Afghan government.

When speaking to displaced villagers in Jalalabad, I heard many similar accounts as the above, in particular regarding free movement in the region. Many even informed me that throughout the conflict, well into the late 2010s, ISKP fighters openly moved at will to and from Bajaur and Khyber Agencies in Pakistan, which neighbor Nangarhar and Kunar Provinces. Further, ISKP had supply lines from the Pakistani Army-controlled Rajgal Valley in Tirah into Achin. It is worth noting that the displaced Kulikhel Afridi natives of this valley had not been permitted to return for over a decade during this same period. If locals could see this, what did the drones in the sky see? This was one of the most surveilled places in the world, so they must have noticed something. However, it is worth noting that early on, these NDS-backed Pakistani militants did not fight the Afghan Taliban. In fact, they maintained friendly relations which would steadily deteriorate until the eventual split. From autumn 2014, these militants began acting much more independently of TTP–although they had already been quite independent and acted in a warlord fashion. This involved setting up checkpoints. Most strikingly, they began to transport massive shipments of armaments from Khyber agency and settling more families from Khyber and North Waziristan. They seemed to be preparing for major conflict.

ISKP Breaks from the Taliban

In May 2015, these militants finally announced their IS allegiance, put up the IS banner, and declared war on the Taliban. Early reactions were very striking:

Mamandis (residents of the valley) remember ISKP’s initial rule from mid-May until early July 2015 as a period of great relief. They initially thought that ISKP was a pro-government force in a new garb and cited the group’s commanders as stating that “we are here to fight the ISI Emirate,” referring to the Afghan Taleban and their link to the Pakistani intelligence service. Their reaction to the ANSF made the new group of old fighters look even more benign to the residents who also cited the ISKP fighters as saying “we have nothing against government forces.” Members of the ANSF who had earlier gone home stealthily and fearing interception from the Taleban, started to roam freely in the area. [...] An Afghan National Army soldier from Mamand told AAN: “We celebrated the coming of Daesh and the disappearance of the Taleban. We could come home and roam around without any fear of being stopped by Taleban.”9

In the summer of 2015, hostilities between ISKP and Taliban passed a point of no return. From then on, the two groups would be at war, which continues to this day. AAN ominously noted: ‘In the following months (and until recently), clashes between the Taleban and the ISKP took up most of the energy that the two groups would otherwise have directed against the Afghan government.’ Many noted the ANA’s failure to engage ISKP in its formative months:

The Pakistani militants did not start fighting the Afghan government immediately after changing their flag. Neither did the ANSF engage in any planned operations against ISKP for two months after its public presence. ANSF and government employees seem to have initially been well tolerated by ISKP, until early July 2015; the fighting in Kot in early June 2015, which killed two ISKP members, one of them after being detained, was reportedly prompted by the police but does not seem to have represented a broader pattern of response on the ANSF’s part. Indeed, in late June 2015, local government and ANSF officials admitted that they were not targeting ISKP fighters. At that time, it seemed as if government officials saw ISKP as a useful tool to undermine the government’s traditional and more powerful enemy, the Taleban. Throughout May and June 2015, in some areas such as Mamand, ISKP went as far as to openly commend the ANSF, as recalled by residents and members of the ANSF from the area.’10

However, hostilities eventually broke out between ISKP and ANA. AAN argues that the most likely reason for this was Ashraf Ghani’s decision to work with Pakistan to target TTP, which enraged Pakistani fellow travelers in ISKP. ‘In this reading of events, Kabul was first to breach the ‘friendship,’ in December 2014.’

2015: Refugee children from Shinwar, Nangarhar describe ISKP’s everyday abuses

I was there a few years later, but still several people insisted that ISKP did not attack ANA forces unless it was for petty disputes over money or armaments. This led me to two interpretations: either ISKP had created a kind of protection racket, through which it extorted local ANA deployments who complied out of cowardice; or ANA forces realized that ISKP had no fundamental opposition to them as they did to the Taliban, so they could be bought off with arms or money to focus on the ‘real’ enemy–in effect, ANA supplied ISKP’s war against Taliban. One person strongly implied the latter interpretation, and another person hinted at it. Both interpretations could be true, but in either case, note that right from the beginning, the Kabul Regime positively engaged with ISKP in a way that it never even considered with the more moderate Taliban. Recall that in November 2001, the regime committed the horrific Dasht e Leilli massacre, in which upwards of 5,000 surrendered Taliban fighters were slaughtered under US supervision. Keep this event in mind.

ISKP in Kabul

ISKP’s emergence wasn’t just a rural phenomenon in Nangarhar. Even before its declaration, the group had adherents in Kabul, as reported by USIP. ‘In summer 2014, months before ISKP was officially announced, translated propaganda materials from the Islamic State’s central leadership were openly distributed in a Salafi mosque in western Kabul following the crowded Eid al Fitr prayers.’11 In the preceding decade, the leaders of this mosque had indoctrinated regular visitors, a dozen of whom at one point began conducting military exercises and fighting alongside the Taliban, starting in 2012. However: ‘When ISKP emerged in 2015, these activists, according to interviews, formed the impetus for the organization, becoming one of the first groups that started recruiting for the ISIS franchise. In subsequent years, some of these leaders would be detained by the National Directorate of Security (NDS), the Afghan intelligence agency. One has been detained several times, but every time he has been freed due to what security officials termed the absence of “solid evidence” and fears of a backlash from the ulema.’12 It’s strange that the NDS–infamous for disappearing/murdering countless innocent people and setting up Contra-style death squads (like the Zero Units)–developed strong legal protocols in the case of known ISKP leaders. Further, prior to August 2021, the Taliban’s presence in Kabul was light. The bulk of attacks were all either claimed by ISKP or had ISKP hallmarks.

For unclaimed attacks, the Kabul Regime the NDS in particular, routinely blamed the Taliban despite scant evidence. These accusations were especially rife during the negotiations for the Doha Agreements. Several attacks even had NDS fingerprints. One infamous incident was the Dasht e Barchi bombing of a Shia girls high school. The school head alleged: ‘Intelligence [NDS] forces came to the school at 10am on the day of the attack to check the security arrangements.’13 I believe him. The Hazara community in Kabul had been consistently failed by the Kabul Regime.14 The police’s behavior after the bombing is extremely revealing of how seriously they took their job: they fled in their trucks, running over some of the girls’ bodies in the escape. Had there been additional ISKP operatives at the location, the surviving students would have been entirely at their mercy.

What is even more disturbing is the social demographics of ISKP’s urban base and its close connections to high places. Members tended to be middle class (often business owners), well educated (often high performers), and non-Pashtun, particularly Tajik–the exact same base as the occupation elite, including the same neighborhoods and home provinces:

A large number of ISKP’s members were raised in comfortable Kabul neighborhoods (and were either born in Kabul or came to the capital from the provinces during their early childhood years) that have no history of support for violent extremist groups; in fact, the same neighborhoods have produced significant numbers of elite government officials. [...]

Almost all members and supporters of the ISKP Kabul cell interviewed, profiled, or cursorily identified during this research came predominantly from ethnically Tajik areas of the three provinces immediately to the north of Kabul: Parwan (most members came from Ghorband District), Panjsher, and Kapisa (most came from Najrab and Tagab Districts). The first two provinces are widely known as anti-Taliban for their tough resistance against Taliban forces in the 1990s. They subsequently contributed a disproportionally large number of elite members of the US-installed government that replaced the Taliban in 2001. With the exception of a minority made up of original Kabulis and a number of Uzbeks from Jawzjan, Takhar, and Faryab Provinces in the far north of the country, the membership of ISKP’s Kabul cell is composed of youth from the areas of muqawamat (anti-Taliban resistance).15

The NDS’s criminal negligence regarding the safety of Kabuli Hazaras reflected broader trends in Afghan society, of which Tajiks are not exempt: anti Shia sectarianism. A big ideological motivator for Kabuli ISKP fighters is Sunni identitarianism: ‘Most of the sectarian rhetoric was directed against Shias, especially Shia political and religious leaders who were accused in blanket terms of advancing Iran’s project of spreading Shiism in Afghanistan. The interviewees blamed the Taliban for sparing Shias from their attacks, thus allowing them to thrive politically and economically. This softer approach to Shias was attributed to the Taliban being a protégée of Iran.’16 In my personal interactions, I found that every Sunni ethnicity was sectarian, but urban dwellers especially so. Many openly stated that Shia are apostates.

Perhaps the most infamous Kabuli member of ISKP is its emir, Shahab al Muhajir aka Sanaullah Ghafari. He became ISKP emir in 2020. His ethnic origins are unclear. I first heard his family had come from India, hence the ‘muhajir’ (immigrant) moniker. Some sources claim that he is an ethnic Tajik, while others claim that he is an ethnic Pashtun. Whatever the case may be, he is a Kabuli Pashto-speaker, which can be instantly detected from his accent. There have been many rumors that Ghafari was bodyguard to NDS chief Amrullah Saleh. Veteran journalist Bilal Sarwary revealed pictures of his ID Card which stated he was a bodyguard but other journalists17 stated there were errors, suggesting it was fake.

ISKP leader Sanaullah Ghafari’s alleged ID card identifying him as a member of NDS chief Amrullah Saleh’s security detail.

It is possible and even likely that the card is fraudulent, but Ghafari’s links to the Kabul Regime’s elite didn’t end there. Combating Terrorism Center, the US military’s counter-terror think tank, reports:

According to two senior security officials of the former Afghan government, al-Muhajir had an extensive social network in Kabul city that helped his recruitment pipeline. This included young individuals from influential political and warlord families who facilitated ISK activities, at times unknowingly [suggesting that they knowingly aided him at other times - R. Ashlar]. Such personal networks helped al-Muhajir logistically, such as acquiring special security cards and weaponry licenses from senior Afghan government officials, including one issued by the office of the former Afghan vice president Abdul Rashid Dostum.18

Mass murderer, serial rapist, sadistic torturer, criminal warlord and former Afghan Republic Vice President Abdul Rashid Dostum

The Case of Mullah Abdul Manan

Perhaps the most obscene link between the NDS and ISKP is a Taliban splinter group led by the now-dead ex-Taliban commander Mullah Abdul Manan. He had joined the movement in the 1990s and had always been a sectarian extremist–he orchestrated the Mazar e Sharif massacre, in which ~8,000 Hazaras were murdered. In 2015, he broke off from the Taliban with a set of fighters. His stated motivation was displeasure with the Taliban’s decision to hide the death of Mullah Omar–the movement founder and spiritual leader–for 2 years, then replace him with Mullah Akhtar Mansour, who was a long time veteran but partially stained by this internal scandal. As a side note, Mansour was a highly effective leader whose internal reforms greatly paved the way for the Taliban’s ultimate victory.

Mullah Abdul Manan, ex-Taliban commander turned NDS asset

What struck most locals about Abdul Manan’s group was that it immediately stopped attacks on ANA forces and focused primarily on the Taliban. It also attacked Shia, leading many to assume he was in the ISKP orbit or had even joined ISKP. All of this instantly raised suspicion and rumors of NDS support. These rumors were confirmed when the NDS went out of its way to rescue Manan when he was gravely wounded. They helicoptered him to a major hospital in Herat for emergency procedures:

Abdul Manan admitted in Herat hospital for emergency surgery, after helicopter rescue by NDS. Credit: https://archive.ph/tgZRg

It goes without saying that the NDS never expended such effort to rescue Taliban commanders. Last year, the Af-Pak conflict news outlet Khorasan Diary revealed a shocking detail about Manan’s group:

ALERT: A key commander of Islamic State Khorasan Province Abdul Malik has been arrested by Counter Terrorism Department [CTD] Sindh in Karachi. A handout by the CTD reads that he had been bankrolling Mullah Abdul Manan group of ISKP in Afghanistan after funds collection in Ramzan [Ramadan]. [Credit: https://archive.ph/bVqBg]

NOTE: While during first interrogation with CTD, the arrested individual stated he was part of ISKP’s Abdul Manan group since 2011, it is worth noticing ISKP formed in 2015, around the same time Abdul Manan split from Taliban [and stopped attacking ANA forces - R. Ashlar]. Abdul Manan never announced support for ISKP. [Credit: https://archive.ph/cooWl]

NDS asset Abdul Manan (center) with confirmed ISKP commander and financier Abdul Malik (circled).

Quite strange.

Helicopter Rescues and Battlefield Aid

The Dasht e Leili massacre characterized the Occupation regime’s extreme hostility to the Taliban, even those who wanted to surrender. The regime was equally hostile to the rural population writ large, the Taliban’s base, whom it subjected to mass state terror in a number of forms. With that in mind, it’s extremely unsettling to contrast it with the regime’s quite lenient approach to ISKP fighters, who it rescued all over the country on a number of occasions when they tried to surrender to escape the Taliban’s wrath. There’s several instances of the ANA rescuing ISKP fighters, oftentimes by helicopter.

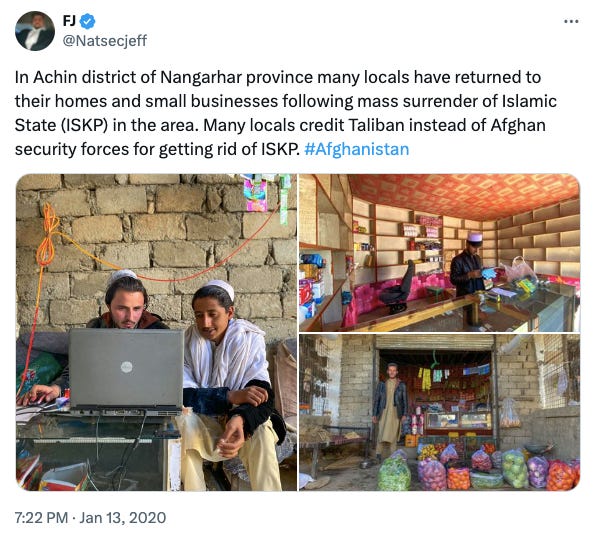

During 2019-20, Kunar and Nangarhar were the sites of a massive showdown between ISKP and Taliban. The fight was brutal, lasting several months but it was a decisive Taliban victory.19 Many key ISKP leaders were killed and their territorial hold eliminated in Afghanistan. Interestingly, during the battle, the ANA’s most notable appearances were routine rescues of surrendering ISKP fighters. On one occasion, Taliban spokesman Zabehullah Mujahid revealed that fighters were helicoptered from mountaintop–local news coverage later confirmed this.20 Allegedly, locals credited the Taliban, but not the ANA, with defeating ISKP in the area:

It’s extremely striking that ISKP fighters already knew the ANA would rescue them, which no Taliban or even civilian could take for granted. The ANA considered ultra-extremist zealots amenable enough to rescue them from their more moderate rival–that is, they perceived them to be a lesser threat than the Taliban:

When fighters arrived in Jalalabad, they were escorted in large convoy with armored vehicles. City residents came out to the streets in droves in clear disbelief:

Credit: https://archive.ph/7pv5I

My translation of street commentary:

Captured Daeshis [ISKP fighters] are coming along, haha…

Look, there’s little kids and women too.

Ahh, he’s right, there’s little kids [in the trucks]!

These are Daeshis.

Incidentally, in 2018, ANA vehicles had donned the IS flag while going through Jalalabad. Locals claimed that they were escorting an ISKP fighter. Kabul Regime forces claimed that it was a trophy from successful operation against ISKP.21

In an undated interview, Afghan MP Zaher Qadir revealed that in two districts of Nangarhar–Shinwar and Chaparhar–ANA forces deliberately aided ISKP against the Taliban. Specificially, he alleged that (1) they intentionally air-striked the Taliban during their battles with ISKP and (2) they allowed ISKP to use ANA bases to attack the Taliban.

Credit: https://archive.ph/XKBod

My translation:

I’ll tell you about a very sensitive subject. In Shinwar, Daesh [ISKP] and Taliban were stuck fighting each other. Over top would come aircraft and it always struck the Taliban but spare Daesh. Then, in Chaparhar, Daesh and Taliban were at war. Whenever Daesh was under strain, they would regroup to ANA bases and from there, strike on the Taliban. I’ve many witnesses – not 1, not 2, not 10, not 20, but more! When the time comes, I’ll bring them and have them go on television so that you’ll listen to what they have to say. They will tell you such stories that you wouldn’t even need any seals, signatures, documents, or stamps as proof.

This follows a number of serious allegations from Qadir in late 2015. ‘KABUL’s first deputy speaker Haji Zahir Qadir on Monday alleged the leaders of Daesh were in Kabul and were supported by the National Security Council (NSC), an allegation the NSC rejected as baseless and far from reality.’22 Indeed: ‘KABUL deputy speaker [Qadir] on Wednesday said the government might collapse if he presented evidence of the National Security Council’s support for the Islamic State (IS) — also known as Daesh.’23 He has never presented this evidence, suggesting it was a bluff, albeit a bold one. Qadir even alleged that there were unknown helicopter landings in eastern Nangarhar, adding that his forces would target them in the future.24 Although there are no known cases of this in Eastern Afghanistan, one such incident in 2018 was filmed and broadcasted on television.

Perhaps the most shocking case in the war on ISKP was the ANA helicopter rescue of ISKP leaders and over 200 fighters in Jawzjan. They had been surrounded by the Taliban, which would have killed them all. One leader, Habib Rahman, gave an oddly amicable interview to local news:

Translation courtesy of Matthew Petti:

In Afghanistan, there are problems–one group fighting another group. They all have justifications. We’re tired of violence and war, and ultimately we’re standing for peace now. We’re in touch with security officials. We’re tired of war and violence and we just want our issues resolved. [Translation breaks off due to Rahman’s strong local dialect. - R. Ashlar].

Here is this same commander giving a press statement at the local NDS HQ:

The fighters were given rice with meat, a luxury for ordinary Afghans, and had demands for personal guards, which were granted.25 The local population was naturally infuriated. Habib Rahman was later imprisoned in Bagram where he denounced ISKP. He has since expressed support for the Taliban, with whom he has given a very interesting interview, in which he cryptically claims that foreign agencies supported ISKP.26 The veracity of this claim is unclear, as the interviewers have every interest to delegitimize ISKP as foreign agents.

Lastly, Afghan liberal newspaper TOLOnews reported mysterious helicopters dropping supplies to militants in Sar e Pol province when it was under ISKP control:

“According to the report we have received from the 2nd Battalion of the Afghan National Army, which fights on the first line of the battle in Sar-e-Pul, two military helicopters landed in a stronghold of the enemy [ISKP] at 8pm last Thursday,” Sar-e-Pul governor Mohammad Zahir Wahdat told TOLOnews. “The helicopters took off after 10 minutes and went towards Sar-e-Pul-Shibirghan Highway, but they could not be filmed due to the darkness of the night,” he added. No further details were immediately available and the identity of the helicopters was not clear.27

This at least partially corroborates ex-prime minister Hamid Karzai’s allegations that he received reports of unknown helicopters dropping supplies to ISKP.

Foreign Financing

In Islamic State in Khorasan, Giustozzi argues that ISKP’s main funding base is donors in the Gulf who turned to the group due to dissatisfaction with the Taliban’s ties to Russia and Iran and overall insufficient zeal. This argument is corroborated by 2019 US Treasury sanctions against an Afghan Salafi NGO. The press release is worth quoting at length:

The Nejaat Social Welfare Organization has materially assisted, sponsored, or provided financial, material, or technological support for, or goods or services to or in support of, ISIS-K [aka ISKP].

Nejaat was used as a cover company to facilitate the transfer of funds and support the activities of ISIS-K.

In late 2016, Afghan leaders of ISIS-K held planning meetings under the cover of a Salafi solidarity meeting sponsored by Nejaat. Executive members of Nejaat and prominent Salafi leaders in Afghanistan led the meeting, some of whom were financial supporters of Nejaat. Rohullah Wakil, also designated today, was one of the executive members of Nejaat who co-led the meeting.

In mid-2016, an ISIS-K facilitator managed a non-governmental organization called Nejaat. An ISIS-K recruiter worked at Nejaat and recruited ISIS-K fighters in Kabul and arranged for their travel to Nangarhar Province.

Nejaat collected donations on behalf of ISIS-K from individuals in Qatar, the United Arab Emirates, Iraq, and other Middle Eastern countries. Money was then transferred from the Gulf to Asia—via the banking system—where an ISIS-K coordinator would collect the transferred funds. Nejaat’s offices in Kabul and Jalalabad distributed the funds to ISIS-K commanders.28

This helps explain a number of very puzzling facts about the group, like their high salaries for fighters, superior equipment and armaments, and overall high quality logistics. In older media releases, fighters can be seen wearing uniforms which cannot be ANA surplus or refitted uniforms:29

2017: ISKP fighters graduate from the Omar al-Shishani training camp in Kunar–note their uniforms. Many of these fighters would later be killed by the Taliban and some may have been rescued by the ANA.

These must be custom, which not only calls into question the broader supply chain, but also surveillance of this supply chain. How did the NDS fail to notice large orders for custom fighter uniforms? One would think that they would sound the alarms upon seeing these orders in a country with active insurgencies. Another especially disturbing example of ISKP’s better funding is their mining operations, which Global Witness reports had better equipment, higher wages for workers, and even hired specialists.30 Despite being much smaller and newer than the much more established Taliban, ISKP was able to finance all of this quite well. Note that Global Witness has since deleted these reports from its website (though I have saved local copies).

Amrullah Saleh

The NDS has come up a lot in this discussion. During this entire period, its leader was Amrullah Saleh, an ethnic Tajik and war criminal. He has the dubious honor of being among the most malevolent figures during the occupation, right alongside Abdul Rashid Dostum and Ashraf Ghani. ISKP grew to major prominence in Kabul right under the NDS’s nose, suggesting either gross incompetence or malicious intent. For many attacks, including those claimed by ISKP, Saleh blamed the Taliban despite not fitting the profile and having exact opposite claims from the perpetrators. One case suggests quite nefarious intent.

On 2 Nov, 2020, ISKP bombed Kabul University. In the preceding months, they had made similar attacks. The Taliban immediately denied responsibility for the 2 Nov attack and Amaq News Agency (offical IS outlet) claimed the attack. Despite all of this, Saleh insisted the Taliban was responsible. Around the same time a soon-debunked video was released of supposed ISKP fighters denouncing the attack (which to my knowledge has never happened). Also around the same time, banners protesting the Doha peace talks emerged out of nowhere. In all, it looked as if Saleh was whitewashing ISKP to keep the war going, thus ensuring his place in power.31 It is worth noting that throughout his career in the Occupation, Saleh’s work was characterized by general incompetence and bloodlust.32 The CIA broadly speaking did not take him seriously, which is why he today languishes in irrelevance in Tajikistan rather than the US, like some other Occupation regime ghouls. Meanwhile, many ex-NDS commandos have been found to have joined ISKP.33 Strange.

END

Unless otherwise stated, all details in this paragraph are extracted from: Borhan Osman, ‘Bourgeois Jihad: Why Young, Middle-Class Afghans Join the Islamic State,’ United States Institute of Peace, 1 June, 2020. Link: https://www.usip.org/publications/2020/06/bourgeois-jihad-why-young-middle-class-afghans-join-islamic-state

Bette Dam, ‘The Secret Life of Mullah Omar,’ Zomia Center, 10 March, 2019. Link: https://zomiacenter.org/reports/report-the-secret-life-of-mullah-omar

Abdul Sayed, Pieter Van Ostaeyen, Charlie Winter, “Making Sense of the Islamic State’s War on the Afghan Taliban,” Hudson Institute, 25 January, 2022.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Unless otherwise stated, all details and quotations in this paragraph are extracted from: Borhan Osman, “The Islamic State in ‘Khorasan’: How it began and where it stands now in Nangarhar,” Afghanistan Analysts Network, 27 July, 2016. Link: https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/en/reports/war-and-peace/the-islamic-state-in-khorasan-how-it-began-and-where-it-stands-now-in-nangarhar/

Interestingly, Lashkar e Islam later broke with ISKP and was among the first to wage war on the group. This was due to Mangal Bagh’s refusal to give baya or loyalty to ISKP, which they demanded. Lashkar e Islam thus began fighting ISKP in Achin. Their offensive proved so successful that it even provided room for the Taliban to begin operating against ISKP.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Borhan Osman, ‘Bourgeois Jihad’

Ibid.

The video seems to have been deleted but Asfandyar Bhittani quoted the key line: https://archive.ph/eWoQK

Ali Yawar Adili, ‘A Community Under Attack: How successive governments failed West Kabul and the Hazaras who live there,’ Afghanistan Analysts Network, 17 Jan., 2022. Link: https://www.afghanistan-analysts.org/en/reports/war-and-peace/a-community-under-attack-how-successive-governments-failed-west-kabul-and-the-hazaras-who-live-there/

Borhan Osman, ‘Bourgeois Jihad’

Ibid.

Cf. Mukhtar Wafai, “Was the leader of Daesh Khorasan a special bodyguard of Marshal Dostum?” Independent Persian (in Farsi), 24 November, 2021. Link: https://archive.ph/rJZLL

Amira Jadoon, Abdul Sayed, Andrew Mines, “The Islamic State Threat in Taliban Afghanistan: Tracing the Resurgence of Islamic State Khorasan,” CTC Sentinel 15, no.1 (January 2022)

It was documented in real time by alleged Pakistani intelligence asset Natsecjeff on twitter. I strongly encourage readers to go through these threads:

Kunar: https://threadreaderapp.com/thread/1141243779413958656.html [archive: https://archive.ph/zblUN]

Nangarhar: https://x.com/Natsecjeff/status/1143618796441276417 [Thread Reader isn’t working here for some reason, so this unstable link will do for the time being.]

Ibid.

“Daesh leaders in Kabul under NSC patronage: Qadir,” Pajhwok Afghan News, 23 November, 2015. Link: https://archive.ph/NIGuF

“Government will collapse if I present evidence: Qadir,” Pajhwok Afghan News, 2 December, 2015. Link: https://archive.ph/CZljn

“Unknown helicopters to be targeted if seen, warns Qadir,” Pajhwok Afghan News, 28 December, 2015. Link: https://archive.ph/Ojn31

Najim Rahim, Rod Nordland, ‘Are ISIS Fighters Prisoners or Honored Guests of the Afghan Government?’ New York Times, 4 August, 2018. Link: https://web.archive.org/web/20180819042230/https://www.nytimes.com/2018/08/04/world/asia/islamic-state-prisoners-afghanistan.html

“Military Choppers Land In Sar-e-Pul ‘To Equip Militants’,” TOLOnews, 11 May 2017. Link: https://archive.ph/reGu3

“Treasury Designates ISIS Financial, Procurement, and Recruitment Networks in the Middle East and South Asia,” US Department of Treasury, 18 November, 2019. Link: https://archive.ph/M6fTO

Thomas Joscelyn, “Islamic State’s Khorasan ‘province’ claims responsibility for attack on cultural center in Kabul,” Long War Journal, 28 December, 2017. Link: https://www.longwarjournal.org/archives/2017/12/islamic-states-khorasan-province-claims-responsibility-for-attack-on-cultural-center-in-kabul.php

“‘At Any Price We Will Take the Mines’: the Islamic State, the Taliban, and Afghanistan’s White Talc Mountains,” Global Witness, May 2018. Also see: “War in the Treasury of the People: Afghanistan, Lapis Lazuli, and the Battle for Mineral Wealth,” Global Witness, June 2016.

Yaroslav Trofimov, “Left Behind After U.S. Withdrawal, Some Former Afghan Spies and Soldiers Turn to Islamic State,” Wall Street Journal, 31 October, 2021. Link: https://web.archive.org/web/20211101181011/https://www.wsj.com/articles/left-behind-after-u-s-withdrawal-some-former-afghan-spies-and-soldiers-turn-to-islamic-state-11635691605?redirect=amp

This is fantastic. Keep going. They can't suicide gun all of us. More will carry the torch. I will subscribe soon when I am less broke

The most unexpected part of ISKP is the volume and the bounciness of their hair. That guy looks like he uses Olaplex.