An Outline Political Economy of Sahelian Jihadism

What undergirds jihadi movements in this unhappy part of the world?

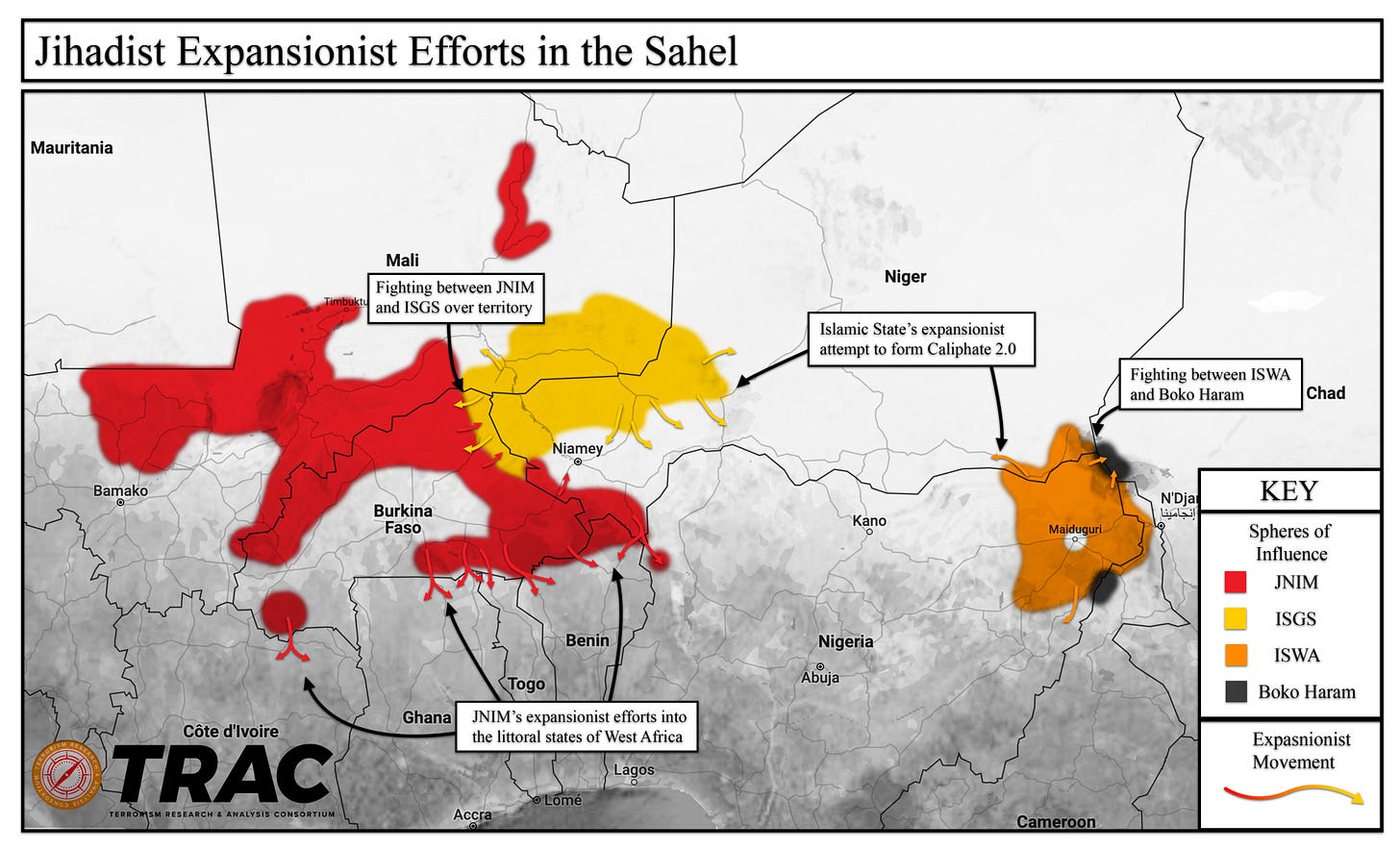

28 June, 2024: TRACTerrorism’s assessment of jihadi spheres of influence in the Sahel. This map is already quite out of date, as JNIM has since established a sphere of influence in Togo and substantially expanded its influence over northern and far western Mali. Its toeholds in northwestern Nigeria and Niger are also growing. Meanwhile, ISGS’s sphere steadily expands in Niger, creeping closer to Niamey. Further, ISGS and ISWAP’s efforts to physically link are well underway. Dire.

Jihadism is the product of broken societies and its adherents and supporters tend to be among the wretched of the earth. In Afghanistan-Pakistan (Khorasan) region, the base of the Taliban has been the rural peasants, who during the American occupation experienced unrelenting state terror. In Iraq and Syria, the base of various jihadi groups were lumpenized workers and rural populations, whose societies were destroyed in civil and imperialist wars. In the Sahel, the base of Jama'at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) and Islamic State-Greater Sahara (ISGS) is de-landed peasants and herders. In all cases, they are the desperately poor in need of relief and taking it (illusory and ephemeral) where they can find it–in a white or black banner. Jihadism is therefore a distorted cry of the oppressed.1 This makes its evils more troubling. If we want to stop jihadism, then the people who comprise or support these movements cannot be reduced to amorphous evil. The structures that produce them and how they understand these structures must be understood. Only this will lead to a humane strategy of combating jihadism, one which adequately stops its barbarism without leveling entire countries to rubble. A politics that ends up supporting systematic air-bombing has clearly gone wrong. It must be remembered that the genocide in Gaza was preceded by a drama that spanned much of the Muslim world, which still must be analyzed.

Peter Linebaugh once observed: “The same moment of struggle in German agrarian relations [Prussian wood theft laws of the 1840s] produced contradictory results among those attempting to understand it: on the one hand, the formation of criminology, and on the other, the development of the revolutionary critique of capitalism.”2 It is striking that the spread of jihadism has produced pro-imperialist ‘jihadology,’ but no anti-imperialist counterpart. Nearly all serious analysis of jihadism is therefore written in service to the systems that produce it. This material is highly valuable but its right-wing allegiance creates limitations. The structures undergirding jihadism are still unclear, even for old conflicts like the Iraqi or the Afghan insurgencies, let alone recent ones, such as in the Sahel.

The Sahelian jihadism crisis is enormous yet it receives scant coverage in mainstream media, let alone left media. There was some buzz during July 2023 when the current junta took power in Niger, but this was a blip arising from and resulting in minimal actual engagement with Sahelian politics. The situation is extremely grim as the map above suggests, but there are open questions: What are the structural factors contributing to Sahelian jihadism? What is the political economy of these movements? Why did the French-backed liberal governments and now the juntas fail to stop them? Below is a possible answer, intended to stimulate further discussion.

Land Enclosures

Marx’s writings on Prussian wood theft laws echo on in the Sahel, where jihadi movements are in part motivated by opposition to colonial-era forest and water laws. Beginning in 1900, the French colonial government enacted a number of laws to ‘protect’ the environment. These laws were rooted in Malthusian views of the local population, as expressed in 1922 by one French writer:

For [Auguste] Chevalier, the scourge is the native. “The remedies to be applied are the same everywhere,” he asserts. “1) Bush fires must be banned wherever deforestation is a danger […]. 2) […] Nomadic forest populations must also be fixed and each village assigned a territory from which it cannot deviate […]. 3) It is necessary to demarcate immediately and register certain forests that must remain permanent in the future, and to entrust their conservation and maintenance to a forestry service with sufficient means of action […].”3

This culminated in 1935, when colonial authorities issued a law that effectively seized all ‘unproductive’ (that is, largely pastoral) lands as state property. ‘The forest décret of 1935 defined the authority of the state to protect forests from overuse and to protect and restore forest areas that had become degraded.’4 In the same year, the government formed the Forest Service, whose function was to enforce the 1935 law. This meant forbidding the traditional activities of (mostly Fulani) pastoralists: fresh wood cutting, drywood collection, nut and fruit picking, livestock grazing, managed bushfires, etc.–which all in fact help the environment. Indeed:

From the outset, this service was designed as a paramilitary and repressive structure, whose mission was not to support local populations, but to subdue them. It was also among the police and the military that the first foresters were sought. The main architect of the decree creating this service, André Aubréville, engineer and then inspector general of water and forests in the colonies in the 1920s-1940s, wrote in 1949: "Here, we must change agricultural methods; there, ban all cultivation." And further: "The evil from which Africa suffers has primary causes that are human, only human."5 [emphasis original]

The colonial-era forest laws were inherited by independent Malian governments, which, especially in the 1980s, have made them even more punitive and hostile to pastoralists. This came in the wake of a 1982 IMF structural adjustment plan that defunded all state capacities, except the Forest Service–which expanded in funding and manpower–due to then-prominent international concerns about desertification in the Sahel. “To impress donors, the revised forest law of 1986 was made even more severe [than the 1935 forest law], with extremely high fines compared to the income level in Mali. ‘Oppressive legislation during the eighties, such as high fines on cutting branches and on forest fires, was instituted because the president wanted to appear to be a staunch environmentalist to appeal to foreign aid for project funding.’”6 The legacy of colonialism in Mali was compounded by the global neoliberal assault on the Third World. Pastoralists have disproportionately borne the costs.

The Forest Service is responsible for exacting these costs, which, alongside routine abuses, has made it extremely unpopular with local populations. In one typical case, a Burkinabe forest agent illegally fined a shepherd for cutting a branch in an authorized tract. The fine initially exceeded the value of the shepherd’s entire flock, but was negotiated down to the still-onerous value of three oxen.7 This pattern of abuse is widespread and institutionalized. Indeed: ‘Forest agents were allowed to keep a portion of the fines collected, in addition to all the fines they collected informally without receipts, which further encouraged their rent-seeking behaviour leading the para-military WFS to become a vehicle for “decentralised plunder across the country” and resulting in the WFS topping rural people's hate list [emphasis mine].’8 In eastern Burkina Faso, the dispossession is especially stark:

In this heavily forested region, the state has, over the years, created eleven hunting concessions, ten of which are managed by private concessionaires,9 and two huge protected areas: Arly Park and W Park. The proliferation of these areas, which prevents people from cultivating, hunting and fishing as they please, has sparked frustration and anger against the authorities. "People do not understand why they are being deprived of land that was exploited by their ancestors, and even less so that foreigners can benefit from it," the local elected official continued.10 [emphasis mine]

The comparison to the Prussian wood theft laws is inescapable. However, the Sahelian laws are not turning pastoralists into proletarians nor is it subduing popular resistance to factory life, as with the nascent German proletariat.11 Instead, these laws are lumpenizing pastoralists, whose dispossession aids meager accumulation, as dictated by the IMF.

The jihadis, particularly JNIM, take great advantage of this popular anger by crudely reversing this enclosure. The Forest Service are among their top targets. Dozens, perhaps hundreds, of forest agents have been killed across Mali and Burkina Faso. The rest flee in fear, which leaves these zones open for JNIM to exploit as hideouts, operating bases, training camps, and rearguards into which they can withdraw after attacks. Likewise, upon seizing control, JNIM reverses all restrictions imposed by the forest laws and opens up these areas to popular use. According to one Burkinabe official, their message to locals is: ‘You can return to the forest, it is yours.’12 This message is hugely powerful and has done much to increase JNIM’s popularity–as has its unofficial social rebellion.

Fulani society is rigidly hierarchical, which, due to the Malian state’s inability to empower the low-caste pastoralists, has created ample kindling for social revolt.13 The two lowest castes of Fulani society are the Rimaybe (descendants of freed slaves) and the Matioube (descendants of slaves proper). Both are essentially equivalent and highly disenfranchised. As one Malian local official reported:

Despite the fact that slavery has been officially abolished, the former Fulani masters still dominate the former slaves in the commune. This can be seen on several levels: on the political level, few Rimaybe accept positions of responsibility; on the social level, Rimaybe marry with difficulty with [high-caste] Jallube or Weheebe Fulani. It's true that today, there are a few who have managed to overcome this hurdle, but they are very rare. You also have to distinguish between Matioube [i.e. maccube]–slaves who are still under the domination of their masters–and Rimaybe–freed slaves who have a free spirit. A Matioudo [i.e. maccudo] always lives under his master's orders, he can't decide without consulting his master, he has no field of his own so it's his master who rents him a field with very difficult conditions. We, the authorities, thought that this phenomenon no longer existed in this country, but it was here that I realized that slavery still exists today. […]

Rimbe [high-caste] dominate the Rimaybe in terms of access to arable land. The Rimaybe are obliged to submit to the conditions proposed by their former masters in order to gain access to this arable land. Otherwise, a Diimajo [aka Rimaybe] who has his own field has no need of any Ndimo [i.e. Fulani of free status), as he is self-sufficient. Land rental contracts vary from one area to another. Here, the landowner makes the field and seeds available to the farmer, who would only provide the physical strength to cultivate. At harvest time, both parties share equally. Generally speaking, landowners have an advantage in letting non-proprietors exploit their plots.14

The state’s ignorance of this problem eventually transformed into active complicity in it.

[T]he pastoralists and shepherds [are] socially downgraded and excessively taxed by the jowro'en (sing. jowro), the holders of the rights over the herbages granted in the 19th century by the Islamic state and beneficiaries of the rents for access to the pastures (conngi) [in the Niger Inner Delta]. With the decentralization of 1993 and the election of communes in 1999, these financial resources enabled the jowro'en to run for elected office and thus perpetuate their dominant social and economic position: “from ‘masters of grass,’ they became mayors of communes, thus having a say in the management of ‘grass and land,’” logically leading them to engage in close collaboration with local representatives of the state (prefects, water and forestry officers, etc).15 [emphasis mine]

Further, the jowro'en choose the order in which herds can go to pasture, with rents and bribes being a key means of ensuring first place. This gives them significant power, which is worsened by their integration into the state. However, even honest jowro'en do these practices, as they are often coerced by state officials who demand bribes in exchange for not seizing communal pastures and livestock corridors. Indeed, pastoralists have steadily lost these lands to privatized rice cultivations since 1972, when the Malian state formed the World Bank-funded Office Riz Moptiz (ORM). “People interviewed in the delta in 2006 also stressed that neither farmers nor pastoralists were consulted when ORM confiscated burgu [pasture] land and closed livestock corridors. One jowro said that ORM had robbed his community of land worth many billions of FCFA. He called it ‘an aggressive hold-up’ and added that ‘ORM – it's a disaster’. Another jowro added that ‘everything ORM has done is bad’.”16 It is therefore unsurprising that JNIM takes great advantage of this twin opposition against the state and traditional pastoralist society. As Gilles Holder concludes:

In such a context, the violence of populations oppressed by a servile origin that disbars them from land access, calls into question the traumatic memories of slavery. Their awakening, failing resilience, requires the re-appropriation of the jihadist model as a liberation movement, following the example of the jihad launched by the Peuls [Fulani] in the early 19th century to fight against the Bambara hegemony and slave economy of the State of Ségou. Thus, whatever the depth of the religious faith that motivates the jihadists of the 21st century, and while we must not obscure the stakes of globalized jihadism, the commitment of slaves by descent to violence takes on a fairly precise meaning: to free themselves from their subaltern and dependent status by force, by reappropriating the jihad.17

The language of jihadism has accordingly shifted, as observed in the speeches of top JNIM leader Amadou Kouffa. In the early years, Kouffa’s rhetoric singled out France and MINUSMA as ‘Crusaders’ invading and oppressing Mali, which they sought to re-colonize for the benefit of white people.18 He denounced the Malian state on the grounds that it sided with the invaders. The rhetoric was initially jihadist anticolonialism but has since shifted to jihadist populism. In recent years, Kouffa has denounced the Malian state as such, calling it a ‘Bambara State,’ which has strong historical and ethnic overtones.19 In the early 19th century, the Fulani fought against and defeated the Bambara Empire, replacing it with the Massina Empire, which presided over a period of Fulani ascendancy and empowerment. The Bambara are also one of the major ethnicities in Mali. Kouffa is therefore invoking Fulani identity in two senses, one affirmative–as inheritors of the anti-Bambara jihad–and one negative–as against the ‘Bambara’ Malian state. As I have said across several writings, the motive forces of nationalism and jihadism are often the same–the two ideologies are often different means of expressing the same concerns. Further, Kouffa condemns the power of the jowro’en and the Fulani elite, and the abuses of the Forest Service. His rhetoric often emphasizes that the only way to establish social equality is through an Islamic state and sharia. This message is unsubtly directed to low-caste Fulani (and Tuareg), who are highly receptive to it, especially because JNIM has put it into practice:

With Katiba Macina taking control over the [Niger Inner] delta from 2015, grazing fees to burgu pastures were abolished, which was obviously a popular move among pastoralists. However, in 2018, the jowros complained to the Shoura (the committee of leaders) of Katiba Macina and asked for permission to start collecting fees again, which was granted, although the rates were reduced compared to the past.

Many dryland pastoralists rejected, however, to comply with this decision arguing that the holy Quran states that pastures are a free gift from Allah. They therefore asked for a reversal of the decision, but the Shoura still decided to keep the fees. This resulted in many dryland pastoralists leaving Katiba Macina to join Dawlat il Islamia, which is a group established in late 2019 that has become part of Islamic State in the Greater Sahara.20

Likewise, in 2015, JNIM took control of an area which had long been the site of competition between two Fulani communities, the one high-caste and the other low-caste. The former had historically received support from the (colonial then independent) government. However, in 2016, JNIM sent letters to both communities, siding with the low-caste Fulani’s priority to pasture, which in practice translated to their exclusive right to pasture.21 At the same time, the historical jihad that Kouffa praises installed the very Fulani elites whom he now denounces. His rhetoric about equality and justice is ultimately fleeting–Kouffa provides no real answer to the Fulani poor. JNIM’s social rebellion offers no lasting solution to the plight of ordinary pastoralists, even if it may provide temporary relief. The gap left by revolutionary socialism is unstably filled by jihadism.

In response to the conflict, the state has adopted a strictly ‘security-minded’ approach, ignoring the social and political origins of jihadism among Fulani. The strategy is essentially apolitical and thus fails to address any of the reasons that Fulani may join JNIM. Unsurprisingly, it has failed with devastating consequences for Mali, which has experienced massive increases in jihadi attacks and ethnic violence. The state’s refusal to consider a political approach reinforces the inequities against which many Fulani and Tuareg are rebelling, reproducing the crisis anew. Indeed, the state has at points worsened the violence by forming paramilitaries from the settled Dogon populations, who have engaged in ethnic violence against Fulani.22 In many communities, these paramilitaries use counter-terrorism and the image of Fulani as ‘terrorists’ to justify settling of personal or communal scores. The essentially apolitical view of the Malian (and other Sahelian) state reproduces the worst abuses of Malian society, which only accelerate the growth of jihadism and worsen the country’s security.

Blood Gold

In contrast to agrarian relations, the role of gold extraction in Sahelian jihadism is straightforward: it is perhaps the largest source of jihadi financing. This is a very new development since gold mining in this region is itself a new industry, per International Crisis Group (ICG):

In central Sahel (Mali, Burkina Faso and Niger), gold mining has intensified since 2012 due to the discovery of a particularly rich vein that crosses the Sahara from east to west. […] These recent discoveries come in addition to the gold already mined in Tillabéri (western Niger), Kayes, Sikasso and Koulikoro (southern Mali), and various regions of Burkina Faso, making artisanal gold a hugely important issue in the Sahel. Artisanal production now reportedly amounts to almost half the volume of industrially produced gold: 20 to 50 tonnes per year in Mali, 10 to 30 tonnes in Burkina Faso, and 10 to 15 tonnes in Niger. This represents a total monetary value of between $1.9 and $4.5 billion per year. The bulk is exported to Dubai, which reports $1.9 billion in annual gold imports from these countries (plus Togo). According to Crisis Group estimates, more than two million individuals in these three countries are directly involved in artisanal gold mining: one million in Burkina Faso, 700,000 in Mali and 300,000 in Niger. The number of people employed indirectly could be three times higher.23 [emphasis mine]

The majority of this extraction is unofficial and beyond government oversight, thus cannot be regulated nor taxed. The increase in mining coincided with a significant decline in the kidnapping-for-ransom economy–which had plagued the Sahel for decades–due to the counter-terror and policing campaigns by France and regional states. As a result, jihadi groups, particularly JNIM, turned to artisanal gold, of which they rapidly began to seize control.

Relations between jihadis and miners are fraught, varying from cautious pragmatism to intense violence. In 2019, when gold mining was still a secondary means of financing, ICG reported: “In Burkina Faso’s Soum province, gold miners pay jihadist groups to secure sites. In the areas of Tinzawaten, Intabzaz and Talahandak, in the north of Mali’s Kidal region, the jihadist group Ansar Dine (a member of the Group to Support Islam and Muslims, or GSIM [i.e., JNIM]) does not have an armed presence to secure the site, but levies the zakat (religious tax) upon miners and the rest of the population.”24 However:

Both JNIM and ISGS carry out frequent ambushes, IEDs and armed attacks — and these are becoming more and more prevalent in areas near industrial mining operations. The most notable of these was the complex attack carried out in the Est region of Burkina Faso on 6th November 2019, targeting a convoy of vehicles transporting SEMAFO mining employees, contractors and suppliers. In the attack the leading vehicle was hit by an IED, before gunmen then opened fire on the convoy — at least 37 people were killed, with another 60 wounded.25

The presence of industrial mines brings substantial scrutiny and security. Their operations are monitored and taxed, while the details of artisanal mines are unknown to the government, making them easier for militants to control and exploit. For this reason, jihadis are hostile to industrial mining companies and launch attacks like the one against the SEMAFO convoy. Two years later, in 2021, Financial Times reported that the situation had significantly worsened.26 Many miners endlessly flee jihadi fighters who stop them on the roads or attack and take control of the mines at which they work. In one incident, jihadis massacred over 130 people. According to the same Financial Times report, by mid-2021, gold mining sites and jihadi spheres of influence almost exactly overlapped in Burkina Faso, which has worsened in the three years since.

In an effort to combat jihadism, the Burkinabe government banned all artisanal mining in the affected regions, which has been highly unpopular with local populations due to the enormous importance of gold in the economy. Reuters reports:

“How many people in Burkina Faso can pay the school fees without artisanal mining?” said Moamoudou Rabo, head of a national union of gold miners. “Our economy is gold mining. There is nothing else.”27

Indeed, much of this mining takes place in wildlife reserves and protected areas, which as established above, are extremely resented by locals. Jihadi groups, especially JNIM, open these areas for economic exploitation, which earns them much favor. Further, they police the mining sites, preventing robberies, banditry, and ethnic feuds from taking place. Most importantly, they purchase the gold at going market rates, effectively sustaining local economies.28 Thus, the population becomes structurally dependent on the presence of jihadis. In some cases, they prefer this over Burkinabe government forces such as the VDP (Volontaires pour la Défense de la Patrie), a paramilitary which has been accused of ethnic massacres and other abuses, largely against Fulanis. The situation in Mali is similar but has important differences. The scale of extraction is significantly bigger than in Burkina Faso:

Malian officials have privately estimated the figure to be between 30–50 tons, while recent investigative journalism from France 24 reckoned that at least half of Mali’s gold, over 60 tons, comes from artisanal mines. The most compelling reason to doubt official Malian figures for artisanal production is that other countries claim to import a great deal more gold from Mali than Mali claims to produce. According to the UN Comtrade Database—an online aggregator of international trade statistics—the UAE purchased nearly 81 tons of gold from Mali in 2019.29

Some artisanal mines in Mali are too large to escape government attention: “Bigger extraction sites, such as the Intahaka mine in the northern Gao region, are several kilometers wide and employ thousands of workers as well as bulldozers and other heavy equipment.”30 As alluded to above, the vast majority of this illicit gold is exported to the UAE, whose role in the Sahelian jihadism crisis has largely gone unscrutinized because it is partially overshadowed by another gold-centric Sahelian crisis: the Sudanese Civil War, in which the Emiratis are deeply involved. Indeed, the UAE is the main destination for most illicit African gold, extracted across the continent.31 The UN and human rights NGOs have urged the UAE to trace its gold imports, but it has rebuffed these requests, spuriously claiming that it maintains the highest standards.

The paths by which illicit Sahelian gold is smuggled to the UAE differs per country. Malian gold is flown straight out of the Bamako International Airport, while Burkinabe gold is trafficked through Togo, from where it is shipped to Dubai. The differences in the two supply chains are striking. In Mali:

Buyers in Bamako, often prefinanced with foreign capital, acquire gold nuggets from artisanal miners and smugglers. At the city’s various refining facilities, they melt these nuggets into bars and ship them abroad. By paying off local customs and airport officials, their couriers can easily leave Bamako for Dubai with bars of artisanal gold stowed in their hand luggage. […] Buyers in Dubai prize low-grade bars of African gold since they can keep the other precious metals that are separated out during the refining process—metals such as silver, palladium and platinum can compose ten percent of a bar’s original mass.32

In some cases, foreign buyers from the UAE, Turkey, and Russia go straight to the source, particularly with massive operations like the Intahaka mine. Loosely pro-government militant groups levy their own taxes on gold as per treaties with Bamako. However, jihadis have not signed any treaties so they continue their attacks and unilaterally take proceeds from gold mining.33 The path for Burkinabe gold is more complex. “Gold flows out of Burkina Faso across porous land borders in cars and buses. It is strapped to cattle or hidden in bales of hay attached to bicycles. Miners at Kabonga, in an area near Pama reserved for herders to raise their livestock, said buyers included locals and traders from neighbouring countries, including Ghana, Togo, Benin and Niger.”34 Due to its low taxes on gold exports, Togo is especially popular among smugglers–I suspect that its key role in gold exports in part motivates JNIM’s recent encroachment on the country. In 2018, Togo exported 24 tonnes of gold to the UAE, despite having no native gold of its own.35 Once the gold arrives in the UAE, it is refined then either exported to another country (usually Switzerland, Saudi Arabia, or Turkey) or manufactured into high-end jewelry for sale. Enormous human suffering across the Sahel is embodied in gold necklaces and earrings.

The Sahelian states’ failure to secure their rural countrysides, in large part due to the forest laws, directly contributes to their inability to control and monitor gold extraction. The Burkinabe government has claimed at various points that it is nationalizing the country’s mines, but these gestures are meaningless if most mines are in territories beyond government control. The security situation must improve first, and for this to occur, the governments must make amends to the rural populations. This requires an answer, or a serious attempt at one, to the agrarian question, particularly as it pertains to pastoralists. Only once the governments obtain the trust of the populations most susceptible to jihadism will it be able to fight jihadism as such. At root, this requires adopting a new and explicitly political strategy.36 Unfortunately, it seems that none of the Sahelian states are interested in such a move, with likely grave consequences for the local population.

More intelligent and non-dogmatic Jihadi supporters have said as much. One has even told me that Jihadism requires very poor and highly destabilized societies to succeed since it cannot compete with material prosperity. This highlights the symbiotic but antagonistic relationship between Jihadism and imperialism.

Linebaugh, “Karl Marx, the Theft of Wood and Working Class Composition: A Contribution to the Current Debate”

Rémi Carayol, “Sahel. L’héritage colonial des eaux et forêts, une arme aux mains des djihadistes,” OrientXXI, 28 April, 2021. Link: https://orientxxi.info/magazine/sahel-l-heritage-colonial-des-eaux-et-forets-une-arme-aux-mains-des-djihadistes,4700

Tor A. Benjaminsen, “Conservation in the Sahel: Policies and People in Mali, 1900-1998,” in: Vigdis Broche-Due, Richard A. Schroeder, ed., Producing Nature and Poverty in Africa, (Nordiska Afrikainstitutet, 1998).

Carayol, “Sahel”

Benjaminsen, “Conservation”

Carayol, “Sahel”

Tor A. Benjaminsen, Boubacar Ba, “A moral economy of pastoralists? Understanding the ‘jihadist’ insurgency in Mali,” Political Geography 113 (August 2024).

Carayol’s note: “The privatization of hunting areas benefits local populations only to a very small extent. In the 2007 budget of the Burkinabe State, out of 10.3 billion FCFA (16 million euros) of revenue linked to this activity, 7.8 billion (12 million euros, or 75%) went to concessionaires, 2.2 billion to the State (3,400,000 euros, or 22%) and only 297 million to local authorities (354,000, or less than 3%).”

Carayol, “Sahel”

Cf. Linebaugh, “Karl Marx”

Carayol, “Sahel”

This overall analysis also holds for Tuaregs.

Quoted in: Gilles Holder, “À propos des Peuls « qui ne sont pas nés » : esclavage, djihad et droits humains au centre du Mali,” Afrique Contemporaine 2023/2, no. 276.

Ibid.

Benjaminsen, Ba, '“A moral economy”

Ibid.

Tor A. Benjaminsen, Boubacar Ba, “Why do pastoralists in Mali join jihadist groups? A political ecological explanation,” The Journal of Peasant Studies 46, no. 1 (2019).

Holder, “À propos des Peuls”

Benjaminsen, Ba, “A moral economy”

Benjaminsen, Ba, “Why do pastoralists”

Cf. Tor A. Benjaminsen, Boubacar Ba, “Fulani-Dogon Killings in Mali: Farmer-Herder Conflicts as Insurgency and Counterinsurgency,” African Security 14, no. 1 (2021).

“Getting a Grip on Central Sahel’s Gold Rush,” International Crisis Group, 13 Nov. 2019.

Ibid.

“What are the key threats facing gold mining operations in the Sahel region?,” Fusion Intelligence, 12 July, 2021. Link: https://intellfusion.medium.com/what-are-the-key-threats-facing-gold-mining-b3aa3869effe

Neil Munshi, “Instability in the Sahel: how a jihadi gold rush is fuelling violence in Africa,” Financial Times, 27 June, 2021.

David Lewis, Ryan McNeill, “How jihadists struck gold in Africa’s Sahel,” Reuters, 22 Nov., 2019.

Ibid.

Bruce Whitehouse, “Illicit Flows to the UAE Take the Shine off African Gold,” MERIP 305 (Winter 2022). Also see: Transnational Organized Crime Threat Assessment—Sahel, “Gold Trafficking in the Sahel,” United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime (New York: 2023).

Ibid.

David Lewis, Ryan McNeill, Zandi Shabalala, “Exclusive: Gold worth billions smuggled out of Africa,” Reuters, 24 April, 2019.

Ibid.

Ibid.

Lewis, McNeill, “How jihadists”

“Gold at the crossroads: Assessment of the supply chains of gold produced in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger,” OECD Responsible Business Conduct, 2018.

‘War is politics by other means.’

“Nearly all serious analysis of jihadism is therefore written in service to the systems that produce it.”

You have quite masterfully put words to something that has troubled me since entering the CT field. Appreciate your perspective, looking forward to more analysis

Very, very interesting piece. How does Burkina Faso's agrarian policy compare to Mali's? Do they have a similar Forest Service?

I am also curious to learn how Sankara's government dealt with the pastoral question. Was it addressed at all?