A Story with Few Words: The Unveiling of Ahmed Godane

An analysis of the former Al Shabaab leader

A way to gauge a jihadist organization’s ideology and place in the global jihadist movement is to see what kind of people claim them as their own. In the eleven years since the split between Al Qaida and Islamic State, the fault-lines have largely settled and each supporter base usually exclusively praise their own side. That is to say, AQ supporters will typically glorify only AQ branches, and likewise for IS supporters and IS branches. But sometimes, you’ll encounter “cross-pollination.” Some AQ supporters will praise some IS branches, while some IS supporters will praise some AQ branches. Al Shabaab is an example of the latter case.

From what I have seen, Shabaab is the AQ branch with which IS supporters have the most (relative) affinity, in no small part due to Shabaab’s unmitigated brutality (such as killing an enormous ~500 civilians in a single strike).1 This is rooted in their brand of Salafi Jihadism, which is very close, if not identical, to IS’s ideology. Indeed, many (such as this writer) have wondered why Shabaab remains so fanatically devoted to AQ when it has far more in common with IS. I have found no compelling answer, but all agree that the man most responsible for Shabaab’s adoption of this ideology–and thus their present character as the most extreme AQ branch–is Ahmed Abdi Godane, the organization’s second leader after Aden Hashi Farah Ayro, the founder.

Al Shabaab initially emerged as a special forces unit within the armed wing of the Islamic Courts Union (ICU).2 Their job was to accomplish particularly difficult missions. Despite much misinformation, the ICU was quite mild by jihadist standards. Prominent ICU leader Hassan Dahir Aweys rejected comparisons to the Taliban,3 highlighting the group’s moderate character, best shown by the push for renewed democratic elections. This began to change once Aden Ayro was killed in May 2008 and Ahmed Godane became the leader of Shabaab (he had previously been the General Secretary of ICU).

Under Ahmed Godane’s tenure, Shabaab’s ideological character dramatically shifted from a jihadist-inclined Islamism to an ultra-hardline jihadism quite similar to Islamic State. By all accounts, Godane was a brilliant military leader, which gave him–and therefore his ideology–considerable political power within ICU. At the time, Shabaab led the Somali struggle against the Ethiopian invasion, which had commenced in December 2006 to topple the ICU and prevent its imminent unification of Somalia. This unification was existentially threatening to the Ethiopian state as a unified Somalia would inevitably seek the ethnically Somali Ogaden region in Ethiopia. Although the ICU was destroyed, Shabaab emerged in its wake, dealing Ethiopia a devastating blow.4 Despite successfully repelling the invaders and thus gaining popular mandate to rule, Godane continued pushing Shabaab’s militancy, rejecting negotiations with the official Somali government and commencing attacks in neighboring Kenya. This was motivated by Godane’s AQ-inspired transnational jihadist ambitions, which sought to fight all “enemies of Islam” as opposed to a more nationally bound struggle like that of the ICU. It was during this time that popular views began to sour on Shabaab, increasingly viewing them as senseless terrorists instead of honorable patriots.

This naturally led to opposition within Shabaab (which had absorbed the ICU) and therefore an ensuing power struggle that Godane won. His clique systematically purged all rivals (including veteran leaders like Hassan Dahir Aweys) before eventually gaining total control of the organization. Godane’s brand of Salafi Jihadism won out over the more moderate currents, giving us Shabaab as we know it today.5 What is remarkable is that amidst all of this, Godane was an extremely secretive figure, releasing only audio statements and going to great lengths to avoid a public footprint. He strenuously limited his public appearances, whether in Shabaab’s media or in public venues. Few even knew how Godane looked–until 2017, when Al Kataib Media Foundation (Shabaab’s media outlet) published a film about Godane’s life, titled The Steadfast March of Shaykh Mukhtar Abu Zubayr. The brief five-minute sequence where Ahmed Godane is finally unveiled is a masterpiece in jihadist media, so it is worth discussing at some length.

We begin with a customary Quranic verse, this time from Surah al-Anfal.

{ Remember when you had been vastly outnumbered and oppressed in the land, constantly in fear of attacks by your enemy, then He sheltered you, strengthened you with His help, and provided you with good things so perhaps you would be thankful. } [Quran 8:26]

The implied message about Somalia and Al Shabaab is obvious. Where before the Muslims of Somalia were beset by many enemies, both from within and without, they now had “good things” (Shabaab) for which they “would be thankful.”6 These “good things” are then displayed in a video montage.

The images are of a powerful army of God and Islam that spans Somalia. With every army, there are fallen soldiers, or martyrs, memorialized for their sacrifices. A number are shown in a lengthy montage.

Whether past or present, Somali or foreign, all are represented by Shabaab, which is the culmination of their collective efforts. But all these soldiers need a leader, every army needs a general. Who is he? We get our first glimpse.

He stands at a distance from us, alone amidst the dirt and clay, yet he stands out, wearing all black surrounded by the light tan mud.

The narrator speaks: “The leader at their head was the veteran, the shrewd, the tireless scholar Shaykh al-Mujahid Mukhtar Abu Zubayr, may God have mercy on him.”

We are getting a better view of the “protagonist” but his face is still hidden, his back still turned towards the audience. He walks away from us. The film silently begs the question: Who is this shrouded figure? It cuts to the next shot.

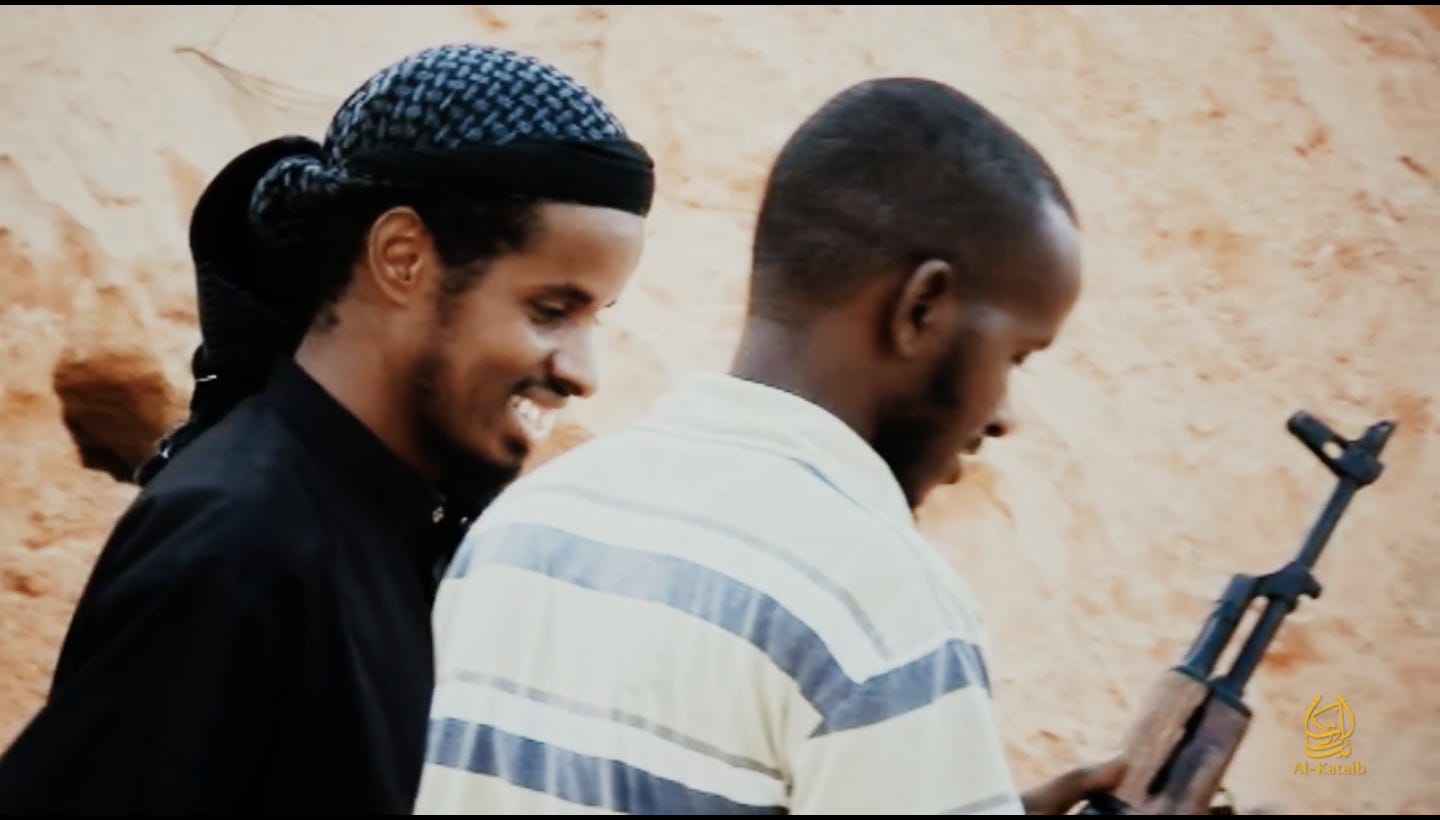

Carrying a rifle, he smiles at an unseen person, but not to the viewer. Mukhtar Abu Zubayr’s face is coming into slightly better view. The smile soon fades from his face. He seems melancholy. What is he thinking? Why won’t he look at us?

It cuts again to the next shot. The “protagonist” now wields his rifle, rusty and well-worn. He is a seasoned fighter. The viewer sees his face, but still only partially. Mukhtar Abu Zubayr is focused on his target, not us. He has more pressing concerns.

And then finally, the audience sees the “protagonist” of the story, unveiled for the first time in history.

There we see him, Ahmed Abdi Godane aka Mukhtar Abu Zubayr. Shabaab freezes on this frame for a few moments. The portrait of the “hero” is complete. He cuts a dashing figure, dressed in all black, carrying a just-used rifle, with a slight smirk on his face. The narrator then tells us that Mukhtar Abu Zubayr was born in Hargeisa in present-day Somaliland, that he was well-educated and intelligent, among other praises of his character. We cut to the next shot.

The “protagonist” breaks character. He is no longer alone but now joking with a friend (who is the friend?). The atmosphere lightens, but there is still some mystery.

Mukhtar Abu Zubayr is now fooling around, no longer so melancholy–but it is only for a few moments.

He puts the rifle away and the screen fades to black. The “hero” returns to the darkness, his black clothes now blending in. These are the final (known) images of Godane ever published. His later appearances in the film are only in audio format, narrating moments of the ICU’s and Shabaab’s history such as the 2006 Battle of Jowhar. With the “protagonist” introduced, we begin to learn about his “steadfast march” and how it intertwined with the history of the global jihadist movement. We soon learn about the anti-Soviet jihad in Afghanistan during the 1980s. We never again see Mukhtar Abu Zubayr on film, but his voice recurs. Something quite striking is that even to a non-Somali speaker (like myself), Godane comes off as incredibly charismatic. It becomes clearer why he was able to turn Shabaab into what it is.

One particularly infamous incident was Shabaab’s stoning to death of a teenaged girl who had been the victim of rape. More recently, Shabaab committed a suicide bombing on a Mogadishu beach, killing over 120 civilians and wounding hundreds more.

The Wikipedia page on the ICU is surprisingly good, in no small part because it was significantly revised by a Somali archivist and researcher whom I personally know and respect.

In many respects, this comparison is still quite justified. The ICU’s origin story is akin to that of the Taliban’s, despite being decidedly more moderate. Both were bottom-up youth movements that emerged in response to the chaos of warlord-driven civil war and then successfully ended warlordism due to their military prowess and reputation as harsh but fair rulers. That said, the difference between the ICU and the Taliban is best seen in the state of girls’ schooling under their regimes: the Taliban ended it after the sixth grade, while the ICU significantly increased it.

By some estimates, upwards of 30,000 ENDF soldiers died in Somalia, with ~10,000 killed in Mogadishu alone. The ENDF body count is notoriously difficult to determine given the Ethiopian state’s extreme secrecy on this subject.

This outline is fairly heavy on “great man history,” but Godane is a striking case of the individual’s role in history. His talents as a military leader gave him the unique opportunity to impose his ideology on the rest of the organization and thus on the Somali militant scene.

Whether many Muslims in Somalia do in fact consider Al Shabaab to be a “good thing” for which they should be “thankful” is an entirely different question. Anecdotally, the opinion is far less glowing than this film would like to suggest.